IP & Corporate Law Updates

- A Guide To Force Majeure Clauses In Different Jurisdictions

- Delhi High Court Permits E-service of Summons and Documents

- Delhi High Court introduces “Public viewing” of Court Proceedings

- Non- Payment of wages amid COVID-19- SC says to negotiate and settle

- Prioritized Examination Program for Covid-19 Related Marks- USPTO

- CBDT extends timelines under taxation and other laws

- Restriction on Patanjali’s Coronil for COVID-19 treatment claims

- PIL For E-Registration Of Documents- Delhi HC Issues Notice To Centre

COVID-19 Updates

- A Guide To Force Majeure Clauses In Different Jurisdictions

- Delhi High Court Permits E-service of Summons and Documents

- Delhi High Court introduces “Public viewing” of Court Proceedings

- Non- Payment of wages amid COVID-19- SC says to negotiate and settle

- Prioritized Examination Program for Covid-19 Related Marks- USPTO

- CBDT extends timelines under taxation and other laws

- Restriction on Patanjali’s Coronil for COVID-19 treatment claims

- PIL For E-Registration Of Documents- Delhi HC Issues Notice To Centre

15 YEARS ON: A RELOOK AT THE INDRP POLICY

By: Vikrant Rana & Deepika Shrivastav

INDRP – Indian Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy & Domain Name Disputes

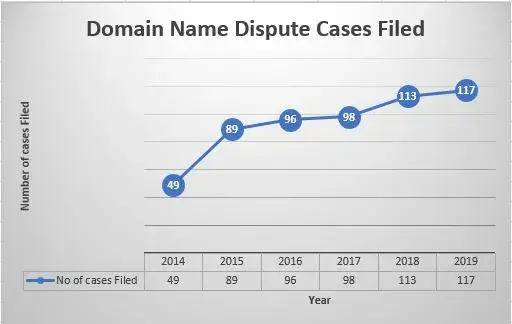

It is no surprise that ever since the recognition of Internet as a tool for advertisement and marketing, there has been a widespread increase in the number of domain name disputes. As per the statistics released by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), there has been a progressive increase in the number of domain dispute cases filed each year since 2013[1]. Similarly, the number of domain dispute cases filed in India with respect to Indian country code top-level domains (ccTLDs) have also seen a remarkable annual increase in the recent years as is evident from the chart below:

A large number of cases from the above can be attributed to cyber squatters who register domains in bulk, thereby, forcing honest and bonafide brand owners to resort to dispute resolution mechanisms so as to recover the domains. Often times, the term ‘virtual property’ is seen being used in conjunction with ‘domain names’ which has alarmed cyber squatters around the globe to get their share of ‘hot property’ and then use it to derive illegitimate monetary benefits by harassing honest and bonafide right owners. At the same time, the surge in numbers, year on year, can be attributed to various other factors including the change in economy, easy access to internet, new and more refined cybersquatting techniques, increasing usage of domain proxy services, and the periodic launch of new generic top-level domains (gTLDs) or country code top-level domains (ccTLDs) in the ever evolving internet world.

In India, domain name disputes relating to (gTLDs) are governed by the Uniform Domain Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP) whereas disputes pertaining to (ccTLDs) are governed by the .IN Dispute Resolution Policy (INDRP) which is overseen and managed by the National Internet Exchange of India (NIXI). The .IN Dispute Resolution Policy (INDRP) was formulated in 2006 following the footsteps of the Uniform Domain Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP) and is in line with the rules of procedure set out by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). However, the INDRP has a few fundamental differences which have been incorporated bearing in mind the requirements inherent to the Indian legal framework. A comprehensive understanding of the differences between the UDRP and INDRP.

The ever growing menace of cyber-squatting can be illustrated by the example of a Registrant/Respondent named “Gao Gou”, purportedly based in Toronto, Canada, The Registrant/Respondent under the said name has been involved in over 16 INDRP cases, which includes domain names such as tatamotors.in, louboutin.in, goodyear.in, sothebysrealty.in, etc. Indeed, one can even say that professional cybersquatting has even assumed the role of a career choice, wherein third parties register hundreds of domains, with the hope that brand owners would be willing to pay them significant sums to recover such domain names.

.IN Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (INDRP)

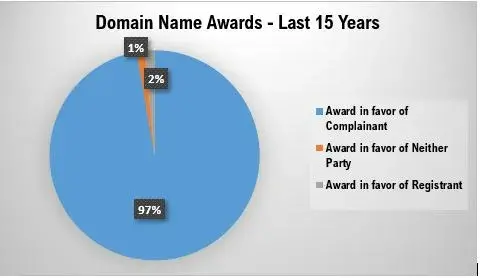

In nearly fifteen years of its existence, NIXI has been able to transparently and efficiently resolve over 1177 matters, thus far[2]. An analysis of the dispute resolution process as well as the judgements passed under the INDRP regime reveals that there has been a slight decrease in the number of decisions passed in favour of the Complainants. A latest analysis conducted for cases filed and decided over the last 15 years revealed that a significant number of decisions (over 97%) were passed in favour of the Complainants/Right holders.

An evaluation of a few notable judgements passed against the Complainant, under the INDRP regime in recent years, aids in understanding the rationale behind the shift in the decision-making paradigm.

Failure to establish the requirements laid down in Paragraph 4, INDRP

Alongside the requirements laid down in Paragraphs 4(i) and 4(ii), INDRP, the ‘bad faith’ requirement as envisaged under Paragraph 4(iii) read with Paragraph 6 of INDRP is one of the most essential pre-requisite to establish malafide intent on part of the Respondent. It may be noted that ‘bad faith’ registration and use of a domain name can be established by showing circumstances indicating that:

- the Registrant has registered or acquired the domain name primarily for the purpose of selling, renting, or otherwise transferring the domain name registration to the Complainant, who bears the name or is the owner of the trademark or service mark, or to a competitor of that Complainant, for valuable consideration in excess of the Registrant’s documented out-of-pocket costs directly related to the domain name; or

- the Registrant has registered the domain name in order to prevent the owner of the trademark or service mark from reflecting the mark in a corresponding domain name, provided that the Registrant has engaged in a pattern of such conduct; or

- by using the domain name, the Registrant has intentionally attempted to attract Internet users to the Registrant’s website or other on-line location, by creating a likelihood of confusion with the Complainant’s name or mark as to the source, sponsorship, affiliation, or endorsement of the Registrant’s website or location or of a product or service on the Registrant’s website or location.

In Tata Motors Limited v. Amit Badyani, INDRP/1020, the Ld. Arbitrator observed that as the Respondent has adopted and registered the mark/domain name prior to the Complainant and has been using the same in respect of a bona fide offering of goods since before receiving notice to the dispute, the Complainant has failed to establish the grounds 4(i) and 4(ii) of the .INDRP policy. With regard to “bad faith”, the Ld. Arbitrator held that the Respondent has not satisfied all the criteria under 4 (iii) and therefore, it cannot be said that the domain has been registered to prevent the Complainant from reflecting the mark HARRIER in a corresponding domain. The Ld. Arbitrator also noted that “mere fear as to what may happen if the Respondent were ever to sell the domain to a third party cannot be the sole criteria for establishing bad faith, especially when bona fide adoption/use has been shown by the Respondent”.

Reverse Domain Name Hijacking (RDNH)

Paragraph 1, UNDR Rules defines Reverse Domain Name Hijacking as using the Policy in bad faith to attempt to deprive a registered domain-name holder of a domain name. The Rules further state that if after considering the submissions the Panel finds that the complaint was brought in bad faith, for example in an attempt at Reverse Domain Name Hijacking or was brought primarily to harass the domain-name holder, the Panel shall declare in its decision that the complaint was brought in bad faith and constitutes an abuse of the administrative proceeding”[3]. It may be noted that while there exists no specific jurisprudence on RDNH under the INDRP, the Tribunals in India have recognized the principal in a number of matters.

For instance, in Tickets Worldwide LLP v. India Portals, INDRP/1187, the disputed domain comprised of the generic word TICKETS. After careful examination of the facts of the case and the evidence placed on record, the panel held that the Complainant has failed to establish any of the requirements laid down under the INDRP. Further, the panel also noted that “the subject matter dispute is a case of Reverse Domain Name Hijacking, given the Complainant’s weak mark and its attempt to misrepresent its date of first use of the mark”. Reverse Domain Name Hijacking was previously held under the INDRP in Computer.in, INDRP/008 wherein the panel had observed that “the tribunal is of confirmed opinion that the domain name, trade name and trademark is a weak mark and absent of proof of fame of widespread recognition of the services provided by the Complainant makes this complaint without cause of action”. In conclusion, the Ld. Arbitrator observed “that the present complaint by the Complainant is a blatant attempt to hijack the domain name of the Respondent and in bad faith to harass the Respondent and to abuse the process of law.”

Other instances where decisions were not passed in favour of the Complainant

Proceedings Dismissed/ Neutral Decisions

Domain disputes are also dismissed on account of the Complaint suffering from inherent deficiencies with regard to the filing requirements or otherwise due to ownership related issues and and hence are dismissed on the grounds of maintainability.

In this regard, in Homeway.com, Inc. v. Ajay Gupta, INDRP/1056[4], the panel held that even though the Respondent has not filed any rebuttal to the Complaint, looking at the facts and circumstances of the case, the Complaint in its present form is not tenable as post the Complainant’s merger with Expedia, Inc., the Complainant are no longer in existence and therefore, lack the locus of filing the said Complaint. However, the Complainant being aggrieved by the Order passed by the panel, filed an appeal before the Hon’ble High Court of Delhi wherein the Ld. Judge set aside the impugned Order and directed the INDRP panel to allow the Complainant to file requisite documents proving ownership on affidavit and to provide an opportunity for an oral hearing before passing the Order. Upon evaluating the additional Affidavit filed by the Complainant and specifically in view of the fact that the Respondent had not challenged the complaint, the Ld. Arbitrator finally decided the matter in favour of the Complainant.

More recently, in Dell, Inc. v Madugula Kartik, INDRP/1059, the panel dismissed the Complaint, under section 25 (c) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, on account of non-compliance with various orders passed by the Tribunal. It is of note that the dismissal of the Complaint in the aforesaid matter was founded on deficiencies in the Complaint filed. Further, the Ld. Arbitrator also observed that the language used by the Counsel was improper and insulting and of the nature that cast aspersions on the Tribunal’s independence and impartiality.

Suspension and termination of proceedings

As per the law laid down under the INDRP, the panel may terminate the arbitration proceeding if, during the arbitration proceedings and before the Arbitrator’s decision, the parties agree to settle the dispute (Settlement or other grounds of termination, Rule 14, INDRP Rules of Procedure).

In this regard, it may be noted that Paragraph 18(a), UDRP Rules, states that “in the event of any legal proceedings initiated prior to or during an administrative proceeding in respect of a domain-name dispute that is the subject of the complaint, the Panel shall have the discretion to decide whether to suspend or terminate the administrative proceeding, or to proceed to a decision”. However, such terminology has not been explicitly used in the INDR Policy and the Rules framed thereunder and it cannot be said with certainty whether it was the legislative intent of the framers to give such an interpretation to the phrase “other grounds of termination”, as used in Rule 14.

Further, while the UDRP identifies settlement of domain name disputes via administrative proceedings to be a mandatory requirement (Paragraph 4(a), UDRP), the nomenclature used in INDRP lacks any such imposition thereby suggesting that concurrent proceedings pertaining to a single domain may be made.

The issue as to whether concurrent proceedings can exist under the INDRP as well as the civil procedure was dealt with at length in Citi Corp And Anr. vs Todi Investors And Anr. 2006 (4) ARBLR 119 Delhi[5]. The contention of the Defendants was that with the formulation of the INDRP, the subject proceedings are liable to be terminated as the dispute of this nature is to be covered under the INDRP and the Rules framed thereunder. The Court observed that “the scheme of the Policy and the Rules framed thereunder, in any case, show that there is no explicit ouster of the jurisdiction of the Civil Court”. It was further noted that “it is well established that where a right pre-existing in common law is recognized by the statute and a new statutory remedy for its enforcement is provided, without expressly excluding the Civil Courts jurisdiction, then both the common law and the statutory remedies might become concurrent remedies leaving open an element of election to persons of inherence”. The Court further held that the whole scheme of the INDRP shows that the remedies available under the said Policy are of an extremely limited nature – “limited to requiring the cancellation of the Registrant’s domain name or the transfer of the Registrant’s domain name registration to the Complainant” (paragraph 12 of the Policy) and “Therefore, by not stretch of the imagination, can it be said that the Policy possesses the machinery by which adequate and complete relief can be provided to the plaintiffs herein.”

Therefore, the INDR Policy and the Rules framed thereunder do not ouster the jurisdiction of civil courts. Accordingly, in cases where relief sought is more than mere cancellation or transfer of domain and where the Plaintiff intends to seek compensation, a civil proceeding may be initiated.

Termination on other accounts

Other instances of termination of arbitration proceedings are seen in cases where there is a lack of prosecution of the Complaint[6] and in cases where all the parties involved are not correctly impleaded. For instance, in Disney Enterprises Inc. v RSADVVM SPT, INDRP/544, the panel observed that “this Tribunal cannot proceed further as there are third party interest involved and the said party is not a party before the Tribunal and the maxim of audi alteram partem restrains this Tribunal from passing any Orders behind the back of a party that too when its’s interest is involved”.

While the shift in numbers cannot be attributed to one specific reason, it can definitely be speculated that the same may be due to the evolution of the INDRP jurisprudence over the years, more sophisticated understanding of the law, NIXI’s continued attempts towards fair, transparent and impartial proceedings to name a few.

Tightening of due diligence – Wrong/Incomplete contact details provided by Registrants

While the above instances illustrate the growing number of cases wherein INDRP panellists have ruled in favour of Respondents/Registrants or have passed neutral orders, there have also been growing instances of INDRP panels tightening the screw on Registrants/Respondents with respect to them providing incorrect contact details while registering the impugned domain names. In many INDRP cases, NIXI/Complainants are not able to successfully serve hard copies of the complaints to the Registrants/Respondents and the couriers as sent return undelivered. This is a common tactic which a professional cyber-squatter might use to keep their personal identities and contact details removed from any legal proceedings. Providing such incorrect information while registering Indian ccTLDs is a violation of paragraph 3(a) of the policy, which stipulates that –

The Registrant’s Representations

By applying to register a domain name, or by asking a Registrar to maintain or renew a domain name registration, the Registrant represents and warrants that:

(a) the statements that the Registrant made in the Registrant’s Application Form for Registration of Domain Name are complete and accurate;

Since 2011, there have been cases wherein INDRP panels have pointed out the violation of paragraph 3(a) of the policy on part of Registrants/Respondent in their awards, including but not limited to the cases INDRP/562, INDRP/606. While this is not a ground prescribed under the INDRP with respect to bad faith on part of the Registrants/Respondents, the mere acknowledgment of the same suggests that the said fact, while looked at in conjunction with the facts and peculiar circumstances of a case, can be used to draw logical inferences to illustrate bad faith.

The above instance suggests that while there has indeed been an upsurge in cases decided in favour of Registrants/Respondents, at the same time there is growing jurisprudence which suggests that minute details like incorrect registration information of Registrants, is being scrutinized while arbitrating matters.

The Conclusion

In conclusion, it is evident that arbitration proceedings, as contemplated under the INDRP, are a much sought after alternative for resolution of domain name disputes for aggrieved parties who do not wish to engage in protracted legal proceedings before courts. Further, from our aforementioned analysis, it is apparent that it is the endeavour of panellists in most domain dispute proceedings under the INDRP regime to pass decisions in favour of honest and bonafide right owners (Complainants or Respondents) so as to discourage cyber squatters from maliciously hoarding domains that they have no legitimate interest in.

Our exhaustive analysis of the INDRP, focusing on the procedural rules, the role of the Registrar, Registrant’s rights etc. Click here to learn more.

[1] https://www.wipo.int/amc/en/domains/statistics/cases.jsp

[2] https://www.registry.in/Policies/DisputeCaseDecisions

[3] https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/udrp-rules-2015-03-11-en

[4] https://www.registry.in/Policies/DisputeCaseDecisions

[5] https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1791092/

[6] Basf-se.in, INDRP/484

For more information please contact us at info@ssrana.com or submit a query.

Read More About Domain Name Dispute in India by clicking on below links.

Evaluation of the .IN DOMAIN Name Dispute Resolution Policy (INDRP) in India

REVERSE DOMAIN HIJACKING- CARE-FULL WHO YOU PICK!

Rules & Regulations related to Domain name in India

CAN CLOUD STORAGE-PORTALS BE ASKED TO PUT IN PLACE A FILTERING MECHANISM TO FERRET OUT INFRINGING MATERIALS?

The copyright infringement and intermediary liability saga continues during Covid-19 times. On June 16, 2020, the Hon’ble High Court of Delhi, was tasked with an urgent interim relief injunction hearing, wherein, the Plaintiff, which is an Education Institution, having chain of coaching centres pan India, filed a suit against a cloud storage company, for the infringement of copyright in its video lectures and booklet material, residing in its server. The hearing was conducted through video conferencing.

Plaintiff’s Contentions and Submissions

The Plaintiff submitted that it is operating coaching centre(s) under the registered trade mark ‘TIME’ and have copyright over the study material in respect to various entrance exams inter alia, including CAT, GMAT, Bank Exam, and GATE. The study material of the Plaintiff is created for the purpose of coaching students who are enrolled with the Plaintiff. Plaintiff became aware of a group named ‘CAT & XAT MBA PREP 2020’ on the instant messaging service ‘Telegram’ wherein, an unknown user has shared links for ‘Time Video Lectures’ and ‘Time booklet material’, which are stored at the Defendants’ cloud storage service called Mega. It was the case of the Plaintiff that the Defendant Mega Ltd. and its co-founders intentionally allowed the violation of the Plaintiff’s copyright in the study material which includes videos concerning lectures and tutorials as also in its registered trademark, by providing storage space on its cloud-based service.

The Plaintiff sought an interim injunction relief against Mega Ltd. and its co-founders to take down all study material of the Plaintiff including such video tutorials, lectures, booklets etc.

The Plaintiff’s Counsel conceded that the two named co-founders of Mega Ltd should be removed from the action.

Defendant’s Contentions and Submissions

The learned Senior Counsel Mr. Prashanto Sen, representing Mega Ltd. made a contention that it is only a cloud-based storage space provider, where the data is end-to-end encrypted using keys generated by the user from their password. Only the user can decrypt its data with the encryption key, generated through its unique and highly secure password.

It was further submitted that Mega Ltd. being an intermediary would fall within the ‘safe harbour’ provisions as enumerated under Section 79 of the Information Technology Act, 2000. Reliance was placed upon the judgements of the Division Bench of this Court in Myspace Inc. vs. Super Cassettes Industries Ltd. and Single Bench judgment in Kent RO Systems Ltd. vs. Amit Kotak.

On coming to know about the two instances of claimed copyright infringement, when it was given notice of the Plaintiff’s Court action, Mega Ltd. immediately disabled those links in line with its published Takedown policy. Furthermore, the Defendant is willing to take down all such links as and when any instance regarding the violation of copyright is pointed out by the Plaintiff.

Further, the Defendant cannot technically, put in place a filtering mechanism to ferret out infringing material as is sought by the Plaintiff in its urgent interim relief application as all stored files are encrypted with keys that are only available to the users.

Court’s Observation

Hon’ble Mr. Justice Rajiv Shakdher, asked the Plaintiff to bring on record its contract with its students that restricts the students from storing Plaintiff’s copyrighted material in any third party source and sharing it.

Secondly, apart from the two instances mentioned in the suit, Plaintiff has not brought to the notice of the Defendant No. 1 any other specific instance of infringing material being uploaded on the Defendant No. 1’s portal.

In view of the aforesaid submissions made by the respective counsels, Hon’ble Mr. J. R. Shakdher opined that the only direction that could be issued in the given scenario is that as and when specific instances of uploading infringing material are brought to the notice of Defendant No.1, appropriate action including taking down of such infringing material will be triggered by Defendant No.1. To facilitate this exercise, the Plaintiff will give instances of URL(s) being used to share such infringing material.

Disclosure: The Defendant Mega Ltd., New Zealand is represented by S. S. Rana & Co., New Delhi.

If you would like to know more about the subjects covered in this publication or our services please feel free to reach out to us at info@ssrana.com.

Related Posts:

Intermediary Liability in India

India: Intermediary’s Liability for Infringing Content

Regulation of Intermediaries in India

U.S. SUPREME COURT GRANTS TRADEMARK PROTECTION TO BOOKING.COM FOR BOOKING SERVICES

By Lucy Rana and Sanjana Kala

Recently, the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Patent and Trademark Office v. Booking.com B. V., No. 19-46 (U.S. Jun. 30, 2020) opined on whether the addition of the generic top-level domain “.com” to an otherwise generic term by an online business would make the same eligible for trademark protection. The mark in question was the term Booking.com used by a travel company with respect to hotel reservation services. The appeal stemmed from the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office’s (PTO) refusal to register the term Booking.com with respect to online travel booking services on grounds of being generic and unprotectable under the law governing trademarks in the U.S. The District Court however ruled that while the term Booking in itself is generic, the addition of “.com” would render it as a descriptive term which (on acquiring a secondary meaning) would make it eligible to be protected as a trademark. The District Court based this finding mainly on a survey report submitted by Booking.com B. V. that was conducted to observe whether consumers recognise the term Booking.com as a brand or as a generic term. As per this survey, 74.8% of the participants identified Booking.com as a brand which was deemed by the District Court as an evidence of acquired distinctiveness. On appeal by the PTO, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit and subsequently the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the District Court’s findings and held that a term styled as “generic.com” being generic for a class of goods and/ or services will be eligible for trademark protection if the term is so recognised by consumers.

Arguments

(TEXT BOX MAYBE INSERTED: Notably the first-ever telephonic oral arguments were presented before the U.S. Supreme Court in this case)

The major bulk of the arguments revolved around the following two aspects:

- Whether granting exclusivity to the term com would give rise to anti-competitive practices in the market, and

- Whether the survey report showing that consumers identify com as a brand was sufficient to lend eligibility to the same as a trademark.

Secondary Meaning of Generic Terms

The PTO submitted that Courts have long held that generic terms for goods and services cannot be protected as trademarks. They argued that given the exclusivity associated with trademarks, online businesses using generic.com terms will be able to monopolize the same by blocking others from using the generic term in relation to their business thereby putting competitors at a disadvantage. The PTO relied on the 1888 Supreme Court decision, Goodyear’s India Rubber Glove v. Goodyear Rubber Co. (128 U.S. 598, (1888) wherein the Court held that mere addition of a designation like “Company” or “Inc.” to a generic/unprotectable term does not create a protectable mark. The PTO likened this to generic.com terms and in fact stated that owing to the functioning of the Internet (where only one entity has the right to use a domain name) granting trademark rights to Booking.com would be even more problematic and give rise to anti-competitive effects in the market.

Booking.com B.V. on the other hand drew the Court’s attention to the principle ensconced in the Lanham Act (also known as the Trademark Act of 1946) which factors consumer perception in determining whether a trademark is protectable and in a way repudiated the 1888 Goodyear case. Further, they stated that granting the term Booking.com trademark protection would not have any anticompetitive effect as Booking.com B.V. has no interest in suing a company that uses a similar domain name as the question of likelihood of confusion/ association among consumers would not arise. In fact, they were seeking registration of Booking.com to prevent counterfeiting, fraud and cyber piracy.

The PTO countered the above by stating that such protection is already provided to unregistered trademarks under the law of passing off and unfair competition, therefore alleviating the necessity of according trademark protection to the term Booking.com.

The Survey Report

The survey was conducted across 400 participants who were presented with seven terms in total — three brand names PEPSI, ETRADE.COM and SHUTTERFLY; three generic words WASHINGMACHINE.COM, SPORTING GOODS and SUPERMARKET along with the term in dispute BOOKING.COM. The survey revealed that:

- 96% of participants identified PEPSI, ETRADE.COM and SHUTTERFLY as brands;

- Less than 1% identified SPORTING GOODS as a brand name whereas none identified SUPERMARKET as a brand name; and,

- While 74.8% of participants identified COM as a brand name, only 33% identified the generic term, WASHINGMACHINE.COM, as a brand.

Booking.com B.V. (in addition to evidence of widespread use) placed reliance on the survey report to prove that consumers recognise Booking.com as a brand. Whereas the PTO observed that the fact that a section of the participants identified WASHINGMACHINE.COM as a brand demonstrates that addition of .com to any generic term is sufficient to give consumers an impression of a legitimate business regardless of whether it exists or not.

Decision

On genericism

The majority 8:1 decision was pronounced by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg holding that:

“Whether “Booking.com” is generic turns on whether the term, taken as a whole, signifies to consumers the class of hotel reservations services. … Consumers do not in fact perceive the term “Booking.com” that way, the courts below determined. … That should resolve the case: because “Booking.com” is not a generic name to consumers, it is not generic.”

Therefore, the principle of primary significance of a trademark illustrated in the Lanham Act was affirmed by the Court, i.e. if consumers perceive a generic.com term as capable of distinguishing the services of a business from members of its class, it would qualify to be a trademark.

On anti-competitiveness

The Supreme Court did not believe that allowing Booking.com to be a registered trademark would give rise to any anti-competitive practices. Re-iterating the PTO’s argument that only one entity can use a particular domain name at one time, the Supreme Court arrived to the conclusion that a generic.com domain has the potential to convey the source of the services to consumers and noted that,

“…a consumer who is familiar with that aspect of the domain-name system can infer that BOOKING.COM refers to some specific entity”

Therefore, the Court agreed with Booking.com B.V.’s contention that the likelihood of confusion among consumers would be less likely for a generic.com domain. Further, the Court propounded that if a competitor has incorporated and is using the generic term in relation to their business, they would be free to do so, as under trademark law descriptive use of a generic term is permitted as long as it is being used “fairly and in good faith” and not as a trademark. Accordingly, the threat of monopolization of a generic.com trademark by a business owner would be mitigated.

On the survey report

The concurring opinion propounded by Justice Sonia Sotomayor clarified that the Supreme Court was not advocating the survey report presented by Booking.com B.V. to be the most persuasive evidence of acquired secondary meaning of a generic term and that the PTO might have been correct in its stance. However this issue was not put to the Supreme Court and therefore they were not obliged to address it.

Dissenting opinion

Justice Stephen Breyer did not agree with the majority decision and sided with the PTO by stating that,

“Terms that merely convey the nature of the producer’s business should remain free for all to use.”

He believed that the majority opinion was disregarding sound trademark policy and such a finding could set a dangerous precedent for businesses who can now obtain trademark protection by merely adding .com to generic names of their goods/ services. Justice Breyer noted that this could give rise to widespread anti-competitive practices in the market. Further, he believed that the majority opinion was undermining the threat of costly litigation by relying on the need to prove actual confusion and the descriptive use defence codified in the statute.

CONCLUSION

The Supreme Court’s rejection of the ‘per-se’ rule has cast the net of trademark protection wide open for generic domain names. Even though Booking.com B.V. claims to hold no interest in suing its competitors, a trademark registration does grant them monopoly over the term Booking.com in respect of hotel booking services. For now, it seems difficult to reconcile the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision with the looming threat of competitive disadvantages that could arise in the market owing to the exclusivity that trademark rights accord to the holder, not to mention the litigation opportunities that this decision may invite in the future. With this judgment, every generic.com owner with the intent of bagging a trademark registration has the right to approach the Courts to see whether their mark crosses the threshold of consumer perception.

Having said this, there is no denying that this judgment is a big step towards the Court’s acknowledgment of the digital era of business which now owing to the COVID-19 outbreak will only acquire more prominence in the life of consumers. This decision might also prove to be a welcome move for brand owners who have invested substantial resources in their business and command considerable popularity in the market. Casting the legal and business ramifications of this judgment aside, the majority opinion does make one thing fairly clear – that consumer is indeed king (or queen!).

Related Posts

15 YEARS ON: A RELOOK AT THE INDRP POLICY

REVERSE DOMAIN HIJACKING- CARE-FULL WHO YOU PICK!

IMPLEADMENT OF MCA IN EVERY INSOLVENCY AND COMPANY MATTERS NOT MANDATORY- NCLAT

In a recent decision passed in Company Appeal (AT) (Insolvency) No. 1417 of 2019, Union of India versus Oriental Bank of Commerce, the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) set-aside the order of the Principal Bench of National Company Law Tribunal, New Delhi,(NCLT), whereby the NCLT directed mandatory impleadment of MCA (Ministry of Corporate Affairs) in all Insolvency and Company related matters.

The NCLAT, upon deliberation of the said order came to an inevitable and irresistible conclusion that such a direction of mandatory impleadment in all cases of Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC) is nothing but beyond the power of the Tribunal and it tantamounts to imposition of a new rule in a compelling fashion.

The Impugned Order

It is pertinent to note that vide order dated November 22, 2019, the NCLT had passed direction to the effect that the Union of India, MCA through the Secretary is to be impleaded as a Respondent party in order to facilitate availability of authentic record by the officers of the MCA for proper appreciation of the matters. The same was made applicable throughout the country and directions were issued to all the benches of NCLT.

Contention by the Appellant i.e. MCA

The MCA through the present appeal, assailed the impugned order of NCLT on the ground that it bristles with numerous infirmities and that the Adjudicating Authority i.e. NCLT was exercising the ‘rule making power’, which was the exclusive domain of the Central Government.

It was further contended that the NCLT passing the impugned order ought to have issued notice to the Union of India, since the subject matter in issue concerns about the imposition of a new rule, which the said Authority has no power to make especially its direction to implead.

While contending about the mandatory impleadment of a party in a suit, the Appellant also relied on Supreme Court’s verdict in the case of Antonio S.C. Preria v. Ricardina Noronha (D) By Lrs.[1], wherein the Apex Court had held that the third person must be heard in the same dispute if he or she has suffered or is likely to suffer any substantial injury by the decision of the Hon’ble Court.

It is was also brought to the notice of NCLAT, that diligent efforts have been made by MCA by issuance of Office Memorandum to all the concerned parties directing them to furnish a list of companies under ‘CIRP, Liquidation and Master Data’.

The Director Legal MCA also pointed out about the provision for separate application under Section 399(2) of the Companies Act, 2013 for production of documents from the Registrar of Companies, and the easy availability of the complete record on MCA 21 Portal on payment of requisite fees.

NCLAT’s Order and Observations

The Hon’ble Three Judge Bench of NCLAT, prima facie made the observation –

“That if a certain thing is to be performed in a particular manner, then the same is to be done in that way. In fact, a procedural wrangle cannot be allowed to be shaked or shackled with”

The Bench then reiterated the axiomatic principle in law in relation to a ‘proper party’ and ‘necessary party’ to a dispute. It further noted that though, the Addition of parties/ striking out parties of course, is a matter of discretion to be exercised by a Tribunal/ Court based on sound judicial principles, the same cannot be exercised in a cavalier and whimsical fashion, and it depends on facts and circumstances of each case.

The Appellate Tribunal further opined that rules of ‘principles of Natural Justice’ are to be adhered to by the Tribunal and opportunity of hearing is to be given to such a third party to explain its stand, as a just, fair and final order can only be passed after hearing the Objections/ Reply of the said party, as non-observance will result in serious miscarriage of justice, besides causing undue hardship.

The NCLAT, went on to observe that in order dated November 22, 2019, the Appellant was not provided with an adequate opportunity of being heard in the subject matter in issue. The NCLAT further took note of the applicability of the impugned order throughout the country, and opined that such a wholesale, blanket and omnibus directions cannot be issued in single stroke.

CONCLUSION

The NCLAT ordered that the impugned order making it applicable throughout the country to all the Benches of NCLT is untenable one and suffered from material irregularity and patent illegality in the eye of Law. In view of the aforesaid observations, the NCLAT held thatthe NCLT has to exercise its discretion of impleading MCA on case-to-case basis, and on sound appreciation of the factual position as well as the basic Principles of law.

[1] (2006) 7 SCC 740

Related Posts

India: NCLAT Interprets disputed debts under the Insolvency Bankruptcy Code, 2016

Cyrus Mistry Moves NCLAT, Challenges NCLT Orders

ERRONEOUS USE OF ARTICLE 32-SC SLAMS PIL SEEKING BAN ON COCA-COLA AND THUMBS UP

By Priya Adlakha and Isha Tiwari

The scope of Article 32 of the Constitution of India has widened tremendously since the ‘Emergency Era’ in late 1970s, as a medium of voicing the rights of indigent population in the country. Article 32 provides a guaranteed right to move to Supreme Court through appropriate proceedings for enforcement of one’s fundamental rights enshrined under Part III of the Constitution. However, the Indian judiciary is witnessing a spike in misappropriation at the hands of litigants, who erroneously invoke this jurisdiction under Article 32 and thus, add to the mounting pile of pending matters. Recently, the Hon’ble Court came down heavily on the Petitioner for erroneously invoking such jurisdiction in the case of Umedsinh P Chavda vs. Union of India and Ors.[1] and imposed cost of Rs. 5 lakhs upon him.

Brief facts of the case

Umedsinh P Chavda (hereinafter as ‘the Petitioner) claiming himself to a social worker, moved the Hon’ble Supreme Court (hereinafter as ‘the Court’) under Article 32[2] of the Indian Constitution, seeking issuance of a writ of Mandamus, against the Union of India (hereinafter as ‘the Respondent’) to pass necessary orders to prohibit the sale and consumption of soft drinks, Coca-Cola and Thumbs Up, and also issue notification uprising people at large not to consume it, as the same is detrimental to the cause of public health and thus, sparked an interesting question of law as to what constitutes as a bona fide reason to file a PIL?

Apart from the above directions, the Petitioner also sought a directive against the UOI, for a complete analytical report and prior scientific approval for a license of such sale and consumption of liquids like Coca-Cola and Thumbs Up.

Supreme Court- Invocation of jurisdiction under Article 32 amounted to ‘an abuse of the process’

The Hon’ble Court observed that though the Petitioner’s affidavit says that the contents of the petition are true to the knowledge and belief of the Petitioner, however the Petitioner has no technical knowledge on the subject. The source of his assertions has not been established. No explanation was given by the Petitioner’s Counsel for targeting two specific brands i.e. Coca-Cola and Thumbs Up. The Court was of the view that the said petition has been filed for extraneous reasons and the invocation of the jurisdiction under Article 32 amounted to ‘an abuse of the process’.

The Hon’ble Bench comprising of Hon’ble Mr. J. D.Y. Chandrachud, Mr. J. Hemant Gupta and Mr. J. Ajay Rastogi, dismissed the said Public Interest Litigation on grounds of being filed without any bona fide reasons and imposed exemplary costs of Rs. 5 lakhs upon the Petitioner, to be deposited with the Registry within one month, as funds for the Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association.

Frivolous Petitions under the garb of PIL

A Public Interest Litigation mandates prima facie violation of fundamental rights of the individuals or the destitute, who lack the means to approach the Court. A PIL cannot be filed as a means of personal vendetta or with an objective of political gain or malice, as observed in the present matter wherein, the impending objective being public health, the same failed to showcase for seeking a specific ban on sale of Coca-Cola and Thumbs Up.

On various occasions, the Hon’ble Supreme Court and High Courts have dismissed such frivolous petitions for extraneous considerations, styled as ‘Public Interest Litigation’, with heavy costs, wherein the Petitioner has its own interest. Following the said trend, in 2019, a Division Bench of the Hon’ble Madras High Court in a case titled as Dhakshnamoorthy vs. The Commissioner[3], hearing a PIL for calling the records of tender notice published by the Commissioner, Tiruvallur Municipality, while dismissing the same, even warned the Petitioner not to indulge in filing frivolous PILs.

Another notable observation from the present matter implies that a Petitioner must possess sufficient knowledge or produce substantial evidence before approaching the Court. This Court in Indian Banks Association vs. Devkala Consultancy Service[4] had allowed the writ petition of a Chartered Accountant on the ground that he was sufficiently knowledgeable, being an expert in auditing and accountancy for pointing out the discrepancies in banks’ policies regarding interest payment. Since the power under Article 32 not only grants an injunctive relief against infringement of fundamental rights but also a remedial relief by way of damages, it has been observed to include within its ambit relief against wrongful invocation of Article 32.

Take away

Constitutional remedies such as Article 32 encompass a wide ambit of power and it has been regarded as a weapon to be used with great care and caution. Though the Article upholds a person’s fundamental rights to their highest regards, there is a fine line which prevents it from encroaching upon the constitutional duties of the State. Doing away with the element of locus standi, by which a person substantiates its right to approach the Court, was regarded by Justice Bhagwati as a strategic arm of the legal aid movement, thus breathing life not only into Articles 21 and 32 but also into Article 39A, which obligates the State to secure justice and legal aid for its citizens[5].

However, it must be regarded that there is no misuse of such a power, even if with the bona fide intention of aiding the indigent and destitute. The legal language leaves a wide room for interpretation as to what constitutes proper invocation of Article 32 and the same may even result in filing of extraneous matters from time to time, but the same must been regarded as to outweigh the implications faced by restricting the judicial review power of the apex institution to secure justice in the face of gross injustice. The route of Article 32 shall be regarded as a speedy remedy for bona fide cause and not as a tool to cause unnecessary vexation and delay justice in significant matters when the Supreme Court already faces a backlog of 60,469 matters[6] and physical hearing being suspended to battle the pandemic of COVID-19, the time of Judiciary demands utilisation in the most judicious manner possible.

[1] Writ Petition(s)(Civil) No(s).346/2020; https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2020/3850/3850_2020_34_21_22517_Order_11-Jun-2020.pdf; accessed on June 23, 2020

[2] Article 32(2) Remedies for enforcement of rights conferred by this Part – “The Supreme Court shall have power to issue directions or orders or writs, including writs in the nature of habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto and certiorari, whichever may be appropriate, for the enforcement of any of the rights conferred by this Part”; https://www.india.gov.in/sites/upload_files/npi/files/coi_part_full.pdf; accessed on June 16, 2020

[3] W.P.No.5027 of 2019 and W.M.P.Nos.5734 & 5735 of 2019

[4] (2004) 11 SCC 1

[5] Article 39A Equal Justice and free legal aid; The Constitution of India ; https://www.india.gov.in/sites/upload_files/npi/files/coi_part_full.pdf; accessed on June 16, 2020

[6] As on March 10, 2020; https://main.sci.gov.in/statistics; accessed on June 16, 2020

Related Posts

GOOGLE PAY IS NOT PAYMENT SYSTEM OPERATOR: RBI TO DELHI HC

Recently, in the case of Shubham Kapaley v. Reserve Bank of India and Ors.,[1] the nation’s central bank i.e. the Reserve Bank of India (hereinafter referred to as ‘RBI’) has submitted to the Delhi High Court that Google Pay is not a payment system operator[2]. In response to the above mentioned case, the RBI has stated that Google Pay is not a digital transaction platform and thus it does not operate any payment systems. In the above case, it was alleged by the Petitioner that Google Pay (popularly known as GPay) was operating without getting any mandatory and requisite authorisation from the RBI.

RBI: Google pay was not operating a payment system as it is third party app provider

In India, the payment and settlement systems are regulated by the Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007 (hereinafter referred to as ‘PSS Act’) which was legislated in December 2007.[3] As per the PSS Act a ‘payment system’ is defined as ‘“a system that enables payment to be effected between a payer and a beneficiary, involving clearing, payment or settlement service or all of them, but does not include a stock exchange. It also includes the systems enabling credit card operations, debit card operations, smart card operations, money transfer operations or similar operations.”[4] Pressing on the above issue, the RBI stated that Google pay was not operating a payment system as it is a third party app provider. A third party app is where a software application is developed and made by a different entity or person other than the manufacturer of the operating system.

The Petitioner in the above case had earlier contended that as Google Pay is not mentioned in the National Payments Corporation of India’s (NPCI) list of authorized payment system operators’ it does not qualify to continue operating payment settlements. The NPCI list referred herein was released on March 20, 2019. Aligned on the same lines, RBI clarified that as it does not operate any payment system, it was placed in the NPCI’s list. However, RBI in this regard has said that the activities carried out by Google Pay is not in violation of the PSS Act.

After the response has been submitted by the RBI, the above case is now listed for further hearing on July 22, 2020. Keep watching this space for more updates on the same.

[1] W.P. (C) 3073/2020, CM APPL.No.10685/2020

[3] https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/PaymentSystems_UM.aspx

[4] Section 2(i) of the PSS Act

ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT ONLINE GAMING BUSINESS IN INDIA

By Rupin Chopra and Reetika Wadhwa

As the world in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic outbreak has witnessed changes in the technological setup by leaps and bounds, the mode of entertainment has expanded its wings to the virtual space entering various domains. Games engaging people of different age groups and belonging to varied strata of society creating interest, excitement, enthusiasm amongst the players have carved out their space in the online world by gaining rapid popularity owing to their attractive components and ready accessibility. Resultantly, while other industries have been severely hit by the pandemic, online gaming business is one of the few businesses which has flourished in these troubled times.

What online games are permitted in India?

The law in India prohibits gambling activities where a person may win or lose merely by the occurrence of an uncertain event or luck (Public Gambling Act, 1867). However, the games requiring the users to exercise superior knowledge; training; attention; experience of some sort are permitted to be offered. In respect of games involving elements of both skill and chance, the ones requiring substantial degree of skill to win are allowed by the law as the same are skill based.

In which States online games are offered in India?

As per the Indian legislation, gaming and gambling are subject matters of the respective State jurisdictions. Prima facie States in India do not prohibit offering of games for real money. However, in some States the games involving exercise of skills of players are not permitted such as Assam[1], Odisha[2] , Telangana[3]

Is there a license for offering online skill games in India?

Online skill games can be offered by obtaining the license in respect of the same issued by the north-eastern State of Nagaland as per the Nagaland Prohibition of Gambling and Promotion and Regulation of Online Games of Skill Act, 2016 and the Nagaland Prohibition of Gambling and Promotion and Regulation of Online Games of Skill Rules, 2016 (hereinafter referred to as the “online game of skills law”).

Which online games are issued license in India?

The online game of skills law grants license for online skill games in respect of those activities which require the players to exert their efforts and skills. Some of the games for which the said license is issued are Chess, Sudoku, Quiz, Rummy, Virtual racing, Virtual sports (Soccer/ Cricket/ Archery/ Snooker/ Bridge/ Pool), Fantasy games, etc. Therefore, in order to win, the players make an effort and approach which is higher than their opponents.

How to obtain the license under online game of skills law?

Upon submission of the application with requisite documents and information and verification of the same by the Director, Nagaland State Lotteries and after complying with the formalities prescribed with respect to the payment of the requisite fees, the license is granted to the applicant, under the online game of skills law, by the Nagaland State lotteries within 6 months from the date of receipt of the application.

What is the applicability of the license under online game of skills law?

The licensee under the online game of skills law can offer their services to all States or Union Territories where games of skills are permitted. License also allows the online websites to advertise their game and gaming services in all such territories where games of skills are exempted from the purview of gambling. The Government access is to be provided to enable the authorities to ensure that the activities undertaken by the licensee are on real time basis.

What is the fees required to be paid for the license issued under online game of skills law?

The license-holder has to pay a gaming tax/royalty of 0.5% of the gross revenue generated, minus any service tax, bonuses, cashbacks, payment gateway charges etc.

What is the validity of license under online game of skills law?

The license would be valid for a period of five years from the date of grant of the license.

As more and more people have now become confined to the four walls of their homes, online gaming business is witnessing a boom with more and more players entering into the market. Offering of games of skills of different nature while abiding by the provisions of the applicable law shall make gaming sector one of the highest revenue generators. The online gaming business is expected to see a new horizon with the easily available hand held devices becoming a common practice and more people becoming interested in the same.

Also read Lockdown- A potential for Online gaming industry

India: Raising the Stakes for Online Gaming

How to offer online games involving stakes in India ?

Nagaland Online Games of Skill Act, 2016

[1] Assam Game and Betting Act, 1970

[2] Orissa Prevention of Gambling Act, 1955

[3] Telangana Gaming Act 1974

State of Bombay v. RMD Chamarbaugwala[ A.I.R., 1957 S.C. 699] – held by the Apex Court of India, Bimalendu De And Etc. vs Union of India (UOI) And Ors. [AIR 2001 Cal 30]

Rule 11 Nagaland Prohibition of Gambling and Promotion and Regulation of Online Games of Skill Rules, 2016

Updates of COVID-19

A GUIDE TO FORCE MAJEURE CLAUSES IN DIFFERENT JURISDICTIONS

By Tulip De and Vibhuti Vasisth

The present pandemic has triggered a range of medical, social and economic consequences around the world. The effects on commerce have turned out to be extremely dramatic. One of the most emerging and frequently asked question is the relating to force majeure clauses in contracts.

The law relating to force majeure differs from one country to another. How and when should one be serving a force majeure notice? What are the available remedies? Whether there exists any other contractual remedy, such as frustration of a contract in a particular jurisdiction or not, and so on. This article provides for some preliminary advice on these issues, among others, across various jurisdictions around the world.

AUSTRALIA

- Whether force majeure is a recognised concept?

In Australia, force majeure would only be available if it is provided for in a given contract. It does not fall under the general law principle and is typically defined as an event which is beyond a party’s control or beyond reasonable control. The purpose of a force majeure clause is to relieve a party of its liability for its inability to perform its contractual obligations due to a force majeure event.

- How can one avail a force majeure remedy?

Force Majeure is only available if it is specified in a Contract.

- What are the essential requirements to claim force majeure?

The general answer is, it depends on the force majeure clause since there are many different forms of it. However, a party willing to rely upon a force majeure event would be required to notify the opposite party of the force majeure event, the nature and cause of the event, its foreseeable duration, the obligations that have been affected, the means proposed to be adopted so as to overcome the effects of such an event and actions that the affected persons have taken or propose to take so as to overcome the force majeure effects.

A party wishing to claim force majeure must also show that it attempted to mitigate the effect(s) of the event on its performance of the contract and that the event could not have been avoided or overcome despite having taken reasonable measures.

- What is the effect of a force majeure certificate issued by a government body?

Force majeure certificates are not issued by Australian Governmental Bodies. In a contract under the Australian law, a certificate issued by a foreign governmental body may work as an evidence that a force majeure event has taken place, but it would not be conclusive unless so provided for, in the given contract between the parties.

- What are the available remedies in case of a force majeure event?

The available remedies in case of a force majeure event are those that are specified in the contract. They may include, but are not limited to: suspension of a parties’ obligations until the event has ceased to prevent performance of such obligations; extension of time in which performance of a contract is required; termination by either or both the parties, if the suspension has continued for a period exceeding a prescribed time-frame.

Clauses more often provide that a force majeure event would not relieve a party from its obligation to pay money.

- Are there any risks associated with an incorrect claim?

Certain risks, such as breach or repudiation of the contract with additional risks of damages, termination, an obligation of specific performance, other contractual remedies, etc., may follow as a consequence of an incorrect claim.

BRAZIL

- Whether force majeure is a recognised concept?

Under the Brazilian Law, force majeure is a recognized concept. It is defined under the Brazilian Civil Code, Article 393.

“393.The debtor is not liable for losses resulting from a fortuitous event or force majeure, unless he has expressly agreed to be liable therefrom.

Sole paragraph. A fortuitous event or force majeure is an inevitable event, the effects of which were not possible to avoid or prevent.”

- How can one avail a force majeure remedy, is it available only when specified in the Contract?

According to the Civil Code, the force majeure would result in the exemption from liability of the debtor even if it has not been specified in a contract, unless the said debtor was already in default at the time the event occurred or in case the said debtor-party had expressly assumed the force majeure risk in the contract.

- What are the essential requirements to claim force majeure?

Where there lies no provision of a force majeure clause in the contract, the Brazilian Law does not prescribe for any key requirements to claim the same. However, the obligation to notify the events of force majeure have been considered as fair and necessary, according to the principle of good faith and trust.

Further, where force majeure is provided in a contract, the key requirements would solely depend upon the wordings and proper interpretation of the concerned clause.

- What is the effect of a force majeure certificate issued by a government body?

Under the Brazilian Law, there exists no prescription for any kind of force majeure certificate, and thus, this issue is not relevant for contracts that are subject to the said Law.

- What are the available remedies in case of a force majeure event?

The following remedies are available in cases where force majeure is not provided in a contract and if a party is able to rely upon force majeure:

- In case of a temporary event, the suspension of the contractual obligations and the exemptions of the liabilities during the relevant period;

- In case of a permanent and/ or irreversible event, the exemption of liability and eventually the termination of the contract without being responsible for the damages resulting from the force majeure event.

When a force majeure clause is provided under a contract and a party wishes to rely on it, the remedies available to the party depends upon the wordings of the force majeure clause, such as:

- That the affected obligations may be temporarily suspended during the period where the force majeure event operates;

- That either or both the parties may become entitled to exercise their right to terminate the contractual relationship;

- That the contract may become automatically discharged, etc.

- Are there any risks associated with an incorrect claim?

A major risk associated with an incorrect claim is that a party believes it is relieved from its contractual performance (either temporarily or permanently) in circumstances where it is erroneous to hold such a belief. In such circumstances, the party wrongly relying on force majeure would leave itself exposed to a claim for breach of its contractual obligations and the Counterparty may even seek potentially significant damages as a consequence of the same.

CHINA

- Whether force majeure is a recognised concept?

According to the General Rules of the Civil Law of the People’s Republic of China[1] and the Contractual Laws of the People’s Republic of China[2], force majeure is a documented concept which refers to any objective-circumstance which can be termed as unforeseeable, unavoidable and insurmountable.

- How can one avail a force majeure remedy, is it available only when specified in the Contract?

Since force majeure is a recognized and collated concept under the People’s Republic of China law, the terms of the contract only define whether a specified event, if occurs, would constitute a force majeure. For instance, if the contracting parties agree that the manifestation of a threatening infectious disease would constitute a force majeure event, then the present outbreak of the coronavirus would also qualify as such.

- What are the essential requirements to claim force majeure?

Where a contracting party wishes to rely on force majeure, such party must prove that the force majeure event led to such party’s entire/partial performance of its contractual obligation becoming impossible.

Additionally, to establishing a causal relationship, it is also important to consider, though on a case-specific basis, the timing/occurrence of the force majeure event and whether the affected party could have undertaken any measure to surmount/ mitigate the said event. These factors would have to be considered by the court so as to determine whether an event is truly unforeseeable, unavoidable and insurmountable by the party in default.

Furthermore, to mitigate the counterparty’s loss, the party in default must, and is under an obligation to notify the counterparty promptly and effectively of its failure to discharge its (agreed upon) contractual obligations, due to force majeure circumstances and to provide proof of such force majeure event (in case required or requested by the counterparty) within a rational time.

- What is the effect of a force majeure certificate issued by a government body?

In the People’s Republic of China, the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (“CCPIT”) is currently offering force majeure shield certificates to People’s Republic of China based companies that are presently seeking to defend an inevitable suspension of performance under their existing contractual obligations, being a resultant of the pandemic outbreak. While the issuance of such certificates may be a cause of alarm to the counterparties that would be/are contracting with the China-based companies, they are not in strictly an official and definitive ruling which may not absolves all of the contractual obligations of such Company. These certificates serve an evidentiary purpose which would ultimately be considered amongst all relevant factors by the court, differing from a case to case basis.

- What are the available remedies in case of a force majeure event?

Subject to the remedies available and specified in the contract, the claimant-party can absolve itself of its partial/entire contractual obligations under the contract which would have been performed by the said claimant-party had the force majeure event not occurred. Where the force majeure event led to the frustration of the entire purpose of the contract, the parties may terminate the contract without finding itself subjected to a forfeiture of any sum.

- Are there any risks associated with an incorrect claim?

When a party fails to perform its contractual obligations basis an incorrect force majeure claim, it would risk breaching the contractual terms and obligations and (may even) face a claim initiated by the counter party for damages.

ENGLAND AND WALES

- Whether force majeure is a recognised concept?

Unlike the positions in various jurisdictions, English law has no inherent or documented definition of force majeure. However, the concept of force majeure is well established and, in general, force majeure events are such events which are beyond the control of a party and which would result in prevention, hindrance or delay in the performance of a party’s contractual obligation.

In due course, the exact definition of force majeure would depend upon the individual terms of the contract.

- How can one avail a force majeure remedy, is it available only when specified in the Contract?

Since there exists no general doctrine of force majeure under the existing English law, none of the terms would be implied unless there is an explicit and valid force majeure clause provided in a contract[3]. Furthermore, case laws have established that by merely referring to a force majeure event in a contract without the term being further and precisely defined would render such clause unenforceable.

- What are the essential requirements to claim force majeure?

The essential requirements that must be satisfied before a force majeure clause may finally be relied upon would depend upon the wordings and interpretation of the concerned clause in question. Usually, the following factors are/should be considered while seeing a force majeure clause:

A. Definition and scope of an event:

First, it ought to be determined whether there is a force majeure event that would fall within the scope of the force majeure clause. Such events may either be expressly included or expressly excluded in the clause.

For starters, a force majeure event is often defined as an event which is beyond the contracting parties’ reasonable control. Some common examples of force majeure events include Acts of God, War, strikes, commotion, acts or threats of terrorism, extreme weather conditions, and so on. More nuanced clauses may also introduce and include a territorial scope to the events.

With respect to the coronavirus outbreak, it has been noted that certain force majeure clauses have also included “epidemic” and/or “pandemic” as a force majeure event. Considering that the World Health Organisation (“WHO”) has declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a pandemic, it is likely that the current outbreak would constitute a force majeure event under the above-mentioned terms.

B. Link between the force majeure event and non-performance:

It must also be shown that the force majeure event caused the non-performance of the contractual obligation.

Under the English law, the party relying on the force majeure clause should be ready to show that the force majeure event is the only cause for non-performance of the contractual obligations. However, the causation thresholds would depend upon and be governed by the exact wording within the force majeure clause.

C. Requirement to mitigate the force majeure event:

Under the English Law, it is also common for force majeure clauses to include mitigation obligations, such as an obligation to exercise “reasonable endeavours/precautions” to mitigate the possible effects of a force majeure event before any party could possibly rely upon the force majeure clause. In any event, the Courts have also found the obligation to mitigate would typically be implied into English law contracts.

D. Requirement to notify counterparties of force majeure events:

The force majeure clause may also impose a notification requirement on the claimant-party. Due Care and diligence should be taken to comply with such obligations so as to avoid future arguments on the efficacy of any notice that has been given.

Due diligence should also be given to the general notification provisions within the relevant contractual terms which are likely to specify the manner and format in which any notification is required to be given.

- What is the effect of a force majeure certificate issued by a government body?

Under the English law, no such provision exists.

- What are the available remedies in case of a force majeure event?

When either of the parties rely upon on a force majeure clause, the relief available to the party depends upon the wordings and interpretation of the clause. For instance:

- That the affected obligations may be temporarily suspended during the period where the force majeure event operates;

- That either or both the parties may become entitled to exercise their right to terminate the contractual relationship;

- That the contract may become automatically discharged, etc.

- Are there any risks associated with an incorrect claim?

A major risk associated with an incorrect claim is that a party believes it is relieved from its contractual performance (either temporarily or permanently) in circumstances where it is erroneous to hold such a belief. In such circumstances, the party wrongly relying on force majeure would leave itself exposed to a claim for breach of its contractual obligations and the Counterparty may even seek potentially significant damages as a consequence of the same.

FRANCE

- Whether force majeure is a recognised concept?

“Force majeure” is a civil law concept which is defined within the French Civil Code, Article 1218.

The said Article states that:

“In contractual matters, there is “force majeure” where an event beyond the control of the debtor, which could not reasonably have been foreseen at the time of the conclusion of the contract and whose effects could not be avoided by appropriate measures, prevents performance of his obligation by the debtor.

If the prevention is temporary, performance of the obligation is suspended unless the delay which results justifies termination of the contract. If the prevention is permanent, the contract is terminated by operation of law and the parties are discharged from their obligations under the conditions provided by articles 1351 and 1351-1”.

Thus, an event prevents a contracting party from fulfilling its obligations under the contract could be qualified as force majeure if it consists of the following (collective) three characteristics:

- the event must be beyond the control of a party and/or the parties, who can no longer perform its contractual obligations;

- the event must have been one that was reasonably unforeseeable at the time of the conclusion of the contract; and

- the event must be such that is unavoidable at the time of the performance of the contract. The unavoidability must make the performance of the contract such, that it becomes impossible for the party/the parties to perform it, and not merely more expensive or more complicated.

The composite of these three characteristics is what results in excusing both contracting parties from executing the contract under its agreed upon terms, as well as from any liability for instances, damages.

- How can one avail a force majeure remedy, is it available only when specified in the Contract?

As mentioned in the preceding paragraph, under the French legal system, application of the force majeure concept is by virtue of law. Force majeure would apply if the above-noted characteristics are met, regardless of whether the contract contains a specific force majeure clause or not.

Further, in the absence of a force majeure clause, the assessment of the force majeure nature of an event is based on the discretion of the presiding judge who has a complete freedom to interpret accordingly, in the matter. It may not be out of place to mention that the judge’s consideration is more often, and generally, highly influenced by the factual circumstances of the case in hand.

It is hence, advisable and preferable to insert within the contract, a force majeure clause, particularly because the parties are at a liberty to either extend, restrict or even list the events and circumstances that would constitute force majeure. These could be either restrictive or indicative in nature.

- What are the essential requirements to claim force majeure?

Where a force majeure clause is inserted in a contract, the key requirements to claim force majeure would solely rely upon the wordings of the clause.

However, in absence of such a clause, the requirements to claim force majeure would be discretionally examined by the presiding judge. Key requirements would be examined either through understanding the scope of the contract or through the sole interpretation and judicial application of mind by the judge:

A. Definition and scope of a force majeure event.

As stated above, the parties are at a liberty to either extend, restrict or even list the events and circumstances that would constitute force majeure. These could be either restrictive or indicative in nature. If a certain event falls within the purview of definition as characterised by the parties, the occurrence of such defined-event is sufficient to characterize the force majeure.

In the absence of a clear definition or a force majeure clause, the judge would be considering whether the three characteristics as stated above are met or not.

In the context of epidemics, French jurisprudence has shown a consistent rejection of force majeure to qualify as such cases. French judges refused to consider the epidemics of H1N1, dengue, ebola or chikungunya as being force majeure occurrences.

However, in the case of the unprecedented COVID-19 outbreak, numerous sanitary measures have been taken by most governments around the globe, including the French government. Multiple declarations from several World organizations and high officials have been issued, which could strongly influence the French Judiciary’s decision while examining a case where a party wishes to invoke force majeure.

B. Link between the force majeure event and non-performance:

Inevitably, a link between the event that the parties consider to be a force majeure event and the impossibility, whether temporary and/or indefinitely, to fulfil their obligations under the contracting terms, would have to be established.

C. Requirement to notify counterparties of force majeure events:

When a force majeure clause is inserted in the contract, these clauses generally include an obligation on the claimant party, to inform the counter party within a specific time period and comply with certain other formalities as laid down in the contract. Should the clause be silent, the presiding judge would be considering the conditions for the force majeure clause’s implementation under the scope of contractual good faith between the parties.

- What is the effect of a force majeure certificate issued by a government body?

Under the French law, neither precedents nor provisions exist in this regard.

- What are the available remedies in case of a force majeure event?

If a party is able to rely upon force majeure, the main consequences will be:

- the suspension of and from the performance in the concerned contract (or in certain cases even termination of the contract) in the event of a temporary disablement due to the existence of the three characteristics, as listed above;

- the termination of the contract in case of a permanent disablement, without any of the parties being held liable;

- The parties are also free to contractually anticipate the consequences of force majeure and define, for instance, whether a force majeure event would result/possibly may result in a temporary suspension or an automatic termination of contract.

- Are there any risks associated with an incorrect claim?

The main risk in incorrectly claiming force majeure is that the defaulting party can be held liable for not carrying out proper due diligence and necessary measures to fulfil its obligations, thus, be held liable for the non-performance of duties under the contract.

In the most unpleasant scenarios, where a claimant party is found wrongfully relying upon a force majeure clause, the opposite party may seek termination of contract for its breach and also seek to get hold of potentially significant damages.

GERMANY

- Whether force majeure is a recognised concept?

According to the German statutory law, the concept of force majeure is not recognized. However, because the parties are generally at liberty regarding the choice of terms and conclusion of the contract, they can mutually agree upon force majeure clauses. Such agreed clause would then define the terms of force majeure and the consequences for the contracting parties.

Nonetheless, the German law does provide for similar solutions at different sections of the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch/ German Civil Code (“BGB”).

There is for instance the concept of “impossibility”/“Unmöglichkeit”, defined under Section 275 of the BGB. The concept of impossibility provides that a debtor may refuse the performance of a contract, if such performance has become impossible for either himself or any other person connected therewith. However, he would be obliged to pay damages if the impossibility was caused by him culpably.

Furthermore, there is also a recognised doctrine of “change in circumstances”/ “Störung der Geschäftsgrundlage”, defined under Section 313, the BGB. This doctrine provides that both parties could demand an amendment to the terms of the contract, in case adherence to the contract under the previous conditions can no longer be reasonably expected from either of the parties. In such a scenario, a party is free to withdraw from the contract, or terminate the contract depending upon the nature of the contract, as a consequence of which all performances would have to be returned.

The German Legislator, on March 27, 2020, voted the “Act to mitigate the effects the COVID 19 pandemic in civil, insolvency and criminal procedure law”. This Act provides and prescribes for a series of amendments in the existing Insolvency and Bankruptcy Law, the Corporate Law, the Criminal Procedure Code and the Civil law.

- How can one avail a force majeure remedy, is it available only when specified in the Contract?

As mentioned in the preceding paragraphs, force majeure is a statutory law in Germany and they do not need to be expressly included in a contract so as to be effective.

- What are the essential requirements to claim force majeure?